On April 9, the Federal Reserve published term sheets for two COVID-19-related “Main Street” lending facilities for companies with both fewer than 10,000 employees and less than $2.5 billion in 2019 revenue. Explained in more detail here, the Main Street New Loan Facility would create a market for bank-originated unsecured loans to companies with modest leverage (not to exceed 4x, net of the new loan) by purchasing a 95% interest in these loans. The Main Street Expanded Loan Facility would facilitate a market in upsized tranches of existing term debt provided the pro forma leverage of the company does not exceed six times 2019 EBITDA.

While these Main Street facilities (as constructed in the April 9 term sheet) would provide direct help some companies, the reality is that the loans described in these term sheets are not particularly risky. Banks are likely making loans to four-times-levered borrowers today, albeit perhaps at higher-than-normal rates. Would-be business borrowers and banks alike have submitted comments to the Federal Reserve and Treasury asking for more flexibility in loan terms: use of adjusted EBITDA, higher leverage tolerances, more flexibility on loan terms, and so on. Borrowers want to qualify for the programs; banks want to maximize the number and volume of loans the Federal Reserve will purchase. Banks are also appropriately concerned about their leverage ratios and their attendant regulatory consequences.

The question is appropriately asked: If the loans offered through the Main Street facilities are relatively low credit risk, how does the government’s goal of supporting lending to mid-size businesses become manifest?

What the Federal Reserve and Treasury may be considering is using the Federal Reserve’s willingness to purchase 95% of certain “safe” loans as a mere backstop for the mid-size borrower loan market. If the Federal Reserve were not required to buy 95% of the least risky loans but would merely offer to buy up to a 95% participation, banks would have comfort that they could offload 95% of nonperforming loans and associated credit loss to the Federal Reserve if necessary. The theory would be that this backstop approach would give bank lenders (and capital markets, to the extent banks securitize or sell off loans) confidence they need to make loans with incrementally more credit risk than they would in today’s conservative market conditions. Banks’ willingness to make loans to companies that exceed the leverage covenants or do not conform to other terms of the Main Street loan facilities would be the product of a “trickle down” effect from the government’s support for the highest-quality loans.

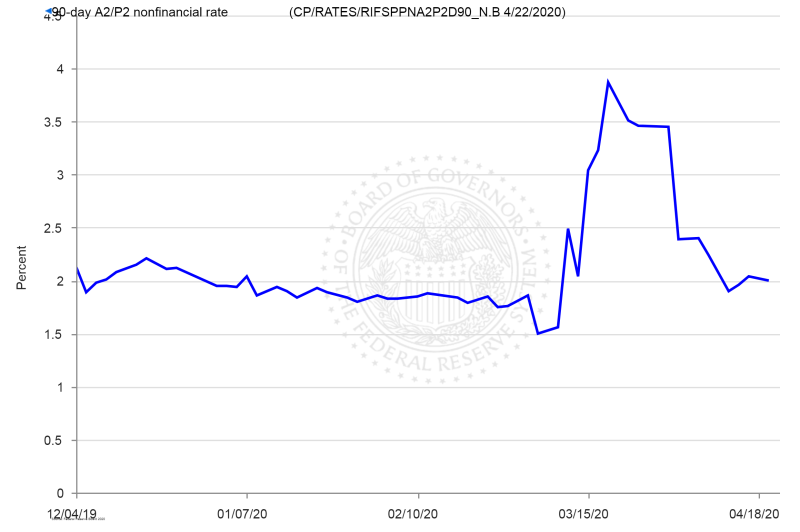

Consider how this phenomenon has worked in the commercial paper and high-yield bond markets. The Federal Reserve’s Commercial Paper Funding Facility, announced in late March and operationalized in mid-April, offers to purchase highest-rated commercial paper; the Primary and Secondary Corporate Credit Facilities, likely to come online later this month, will purchase only investment grade corporate debt (with an exception for investment grade issuers that have recently been downgraded—perhaps a sign that the Federal Reserve is relying slightly less on the predictive quality of credit ratings in an all-world, all-industry economic shock). This chart shows recent pricing in the Tier 2 commercial paper market—a market not directly helped by the CPFF because Tier 2 commercial paper is not eligible for purchase.

Source: The Federal Reserve Board of Governors

As you can see, loans against commercial paper that is riskier than the paper eligible for direct purchase by the Federal Reserve are being made at pre-COVID-19 rates (or better). Similarly, yields on high-yield corporate bonds (those rated BB+/Ba1 through C/Ca) have rebounded to near-pre-COVID-19 yields even though these assets are ineligible for purchase by the Federal Reserve’s Corporate Credit Facilities. Just before these facilities were announced on March 23, the return on the S&P High Yield Corporate Bond Index was 669; today, the return is approximately 760, just 43 points off of its 52-week high of 803, revealing a 68% recovery (note that the Corporate Credit Facilities are not even open for business yet).

If these examples are instructive, the Federal Reserve’s “backstop” approach to the Main Street program should open up the bank lending market, at least incrementally, to borrowers that do not conform to the terms of the Main Street lending programs as banks and their capital markets partners seek higher yield. Still, the Federal Reserve has never operated a program like this for business debt. It is always safer for businesses to have the terms of their unique credit needs qualify directly for Federal Reserve participation, and we advise clients to continue to submit comments to the Federal Reserve and Treasury in pursuit of this effort.

But the above scenario should be understood with a few caveats. First, prudential bank regulation requires banks to hold more capital against riskier loans, which is one of the reasons banks have shrunk their lending footprint in the small- and mid-sized company (SME) loan market over the last ten years. This regulatory pressure, if not relieved, may discourage banks from making riskier loans even with the 95% Federal Reserve take-out in place; if the regulatory pressure is relieved, e.g. through temporary changes to risk-based capital rules, there will be an incremental increase in systemic risk to the financial system. Second, a significant percentage of SME loan volume today is financed by the capital markets, which rely on bank warehouse lines that in turn rely on functioning securitization markets. For SMEs that are not currently bank-financed, the question will be whether banks come in and make term loans that don’t qualify for the Federal Reserve’s Main Street facility support on top of existing capital markets loan facilities. The easier approach would be to allow existing lenders to extend additional credit to borrowers, but this requires access to bank-provided warehouse lines that in turn rely on functioning securitization markets. Currently, the Federal Reserve’s Term ABS Loan Facility (TALF) provides direct support only to AAA-rated collateral; the Federal Reserve will need to provide deeper TALF support if it wishes to facilitate enough warehouse and non-bank lender liquidity to actually help SME businesses that are not presently bank-financed.

Information is changing daily and some of the content included in this alert may have changed or been updated since publication.

Click here to read more Brownstein alerts on the legal issues the coronavirus threat raises for businesses.

This document is intended to provide you with general information regarding two federal “Main Street” lending facilities related to COVID-19 relief efforts. The contents of this document are not intended to provide specific legal advice. If you have any questions about the contents of this document or if you need legal advice as to an issue, please contact the attorneys listed or your regular Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, LLP attorney. This communication may be considered advertising in some jurisdictions.